Action 6.4

Establish a coordinated autonomous vehicle (AV) strategy for the Capital Region

What

There’s an obvious intrigue when it comes to autonomous vehicles (AVs) that can drive themselves without human interaction—because, eventually, they will be on our roads, driving changes to demands on the transportation system and the built infrastructure. Some researchers anticipate that consumers will benefit from a reduction in crashes, emissions, and congestion, while others assume less dense development patterns and a loss in public revenues as a result of widespread AV adoption. In this uncertain time, many agree that, in the absence of strategic planning, regulation, and thoughtfully constructed policies, the future may look like “heaven” or “hell”—or somewhere in between.

Currently, car manufacturers and tech companies are working to make full AVs a reality by expanding upon the five key components of an AV’s anatomy. These include computer vision (cameras), sensor fusion (data collection from surroundings), localization (GPS location), path planning (destination and real-time on road trajectory), and control (vehicle uses all parts independently). As these components continue to be perfected, it will require collaborative efforts by the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT), states, and local jurisdictions to develop regulatory, workforce, and policy standards that can adhere and adapt to the changing environment.

While the Capital Region is still a few years away from widespread adoption of full AVs on the roadway, Maryland, the District, and Virginia differ in their approach to allowing the testing of full AVs on their roads. The jurisdictions within the Capital Region should work together to establish the foundation to leverage this technology to maximize its potential benefit while minimizing its negative impacts.

Why

The arrival of full AVs, which can navigate the roadways in all situations without human drivers, may be only a few years away, but there is much uncertainty on how the technologically advanced vehicles will transform the Capital Region. Many stakeholders assume, with widely differing outcomes, that AVs could significantly change mobility demands (e.g., reduce demand for parking, increase or decrease vehicle miles traveled, increase sprawling development patterns), lower employment in the transportation sector, decrease transportation revenues, and increase safety. It is too early to be confident of the outcomes from AV penetration, but it is nevertheless important that transportation agencies adopt strategies to plan, manage, and maximize AVs’ benefits and reduce their risks to enhance mobility options and convenience for all consumers.

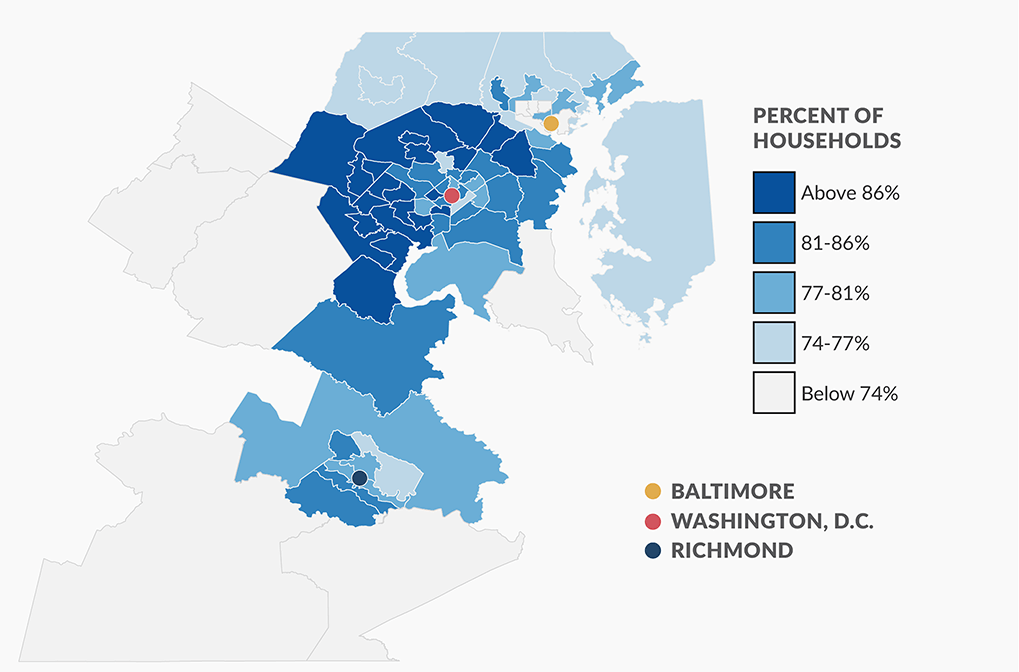

The University of Maryland’s National Center for Smart Growth analyzed a possible future for the Baltimore and Washington metro areas—where autonomous vehicles are adopted widely, where fuel prices are low, and where the governments don’t regulate growth—as part of its Prospects for Regional Sustainability Tomorrow (PRESTO) project.1 Under these conditions, PRESTO found the economy would boom—and vehicle miles traveled would increase 37 percent more than existing projected baseline conditions.2 However, due to AVs’ ability to drive closer together, the roads could carry more vehicles and significantly reduce congestion by 78 percent.3 Under the assumption that driving would be easier and cheaper, PRESTO predicts residential and workforce land uses could sprawl and transit ridership could be cut by 41 percent from current baseline projections.4 While this future depends upon several factors that may or may not occur, decision makers will need new resources and tools—similar to the PRESTO model—to sufficiently plan for and achieve desirable outcomes for the region.

Strategically planning and executing thoughtful policies to deal with AV integration will be important. However, collaboration to create learning opportunities and coordinated AV plans and policies throughout the Capital Region does not yet exist. Maryland, Virginia, and the District are well entrenched in researching AVs and advancing various pilots; however, there is limited coordination between the state departments of transportation (DOTs) or metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs) that would allow for cross-border commuting. The Maryland Department of Transportation (MDOT) enacted a framework through a working group that allows for the testing of Connected and Automated Vehicles (CAVs) and is developing a statewide CAV strategy.5 The District has partnered with the Southwest Business Improvement District (SWBID) to release a Request for Information for an AV pilot program on 10th Street SW.6 Virginia has created the Virginia Automated Corridors (VAC) initiative, which provides multiple real-world testing environments, including over 70 miles of urban interstates and rural arterials in Northern Virginia.7 The Commonwealth is also developing a CAV program,8 which is separate from Maryland’s strategy.

The three jurisdictions’ advancement of innovative approaches to AV testing and planning is a positive step forward. Yet, the region’s transportation demands do not end at state borders, and AV technology—if widely deployed—will need to safely and seamlessly cross into and back from neighboring jurisdictions. In the calm where we find ourselves today, before the likely disruptive storm of AV penetration, the region should learn together and adopt coordinated approaches to AV implementation.

Benefits

While the benefits of AVs are speculative at this point, their potential to impact the transportation system could be significant. More than 37,000 people were fatally wounded by human-driven vehicles in 2016.9 Distracted and drunk driving are two main factors for crashes—both severe and fatal on U.S. roadways10—that may no longer be a factor for AVs. Speed is also a major factor for crashes, which could be removed if policies require AVs to adhere to speed limits. Together, this may lead to a significant reduction in crashes and fatalities.

Additionally, deploying AVs in a shared service vehicles model could reduce household vehicle ownership costs and reduce the amount of public space reserved for parking vehicles.

Barriers

A key barrier is the lack of federal regulations for uniform standards for AVs and supporting technology—creating uncertainty for many private and public actors. Another barrier is that no one knows when AVs will be widely available. In the absence of federal direction and wider adoption in regions throughout the world, states and localities are creating a patchwork of regulations and executive orders to regulate and incentivize AVs while remaining uncertain on how best to plan for the future. This creates challenges for multi-jurisdiction public or private AV testing and best practices to be developed and deployed.

Similar to other new technologies, manufacturers and operators of AVs will be seeking an environment where there are clear regulations and high-quality infrastructure. If we don’t have that in the Capital Region, AVs will be deployed elsewhere—leading to a perception that the Capital Region is not a cutting-edge place, and costing us jobs or people seeking the benefits AVs can provide. If the Capital Region wants to be a place that encourages innovation, it needs to create the environment in which AVs can succeed.

Next moves

One of the most impactful ways the region can improve AV implementation is through increased collaboration. This is not occurring today, which hinders the region’s preparedness for AV adoption.

Next moves are:

- Maryland Department of Transportation (MDOT), District Department of Transportation (DDOT), and Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) should establish a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) to develop consistent and coordinated approaches to plan, deploy, and govern AV technologies; share best practices for pilots conducted in each jurisdiction; and research and implement coordinated responses to potential changes expected from AV adoption, including land use and transportation demand changes, transportation and non-transportation revenue loss, changes to workforce demand and training, changes to traffic rules and regulations, and physical and IT infrastructure

- Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA), Maryland Transit Administration (MTA), and Greater Richmond Transit Company (GRTC) should conduct joint federally funded research pilots to test AV applications

- Each transportation agency in the region should integrate new tech-enabled mobility options into long-range transportation plans and modal plans (e.g., pedestrian, transit, bicycle, and freight), including AVs, rideshare, and dockless mobility options

Costs

The costs associated with planning and coordinating AV efforts are limited and can be built into existing work programs by the governments of the Capital Region.

Expand to learn more

Collapse